More Information

1. Reuther

Rev. Johann Georg Reuther (1861-1914) was a German-speaking Lutheran missionary who was in charge of Bethesda mission at Lake Killalpaninna (near Cooper Creek, east of Lake Eyre, South Australia) from 1888 to 1906. In addition to his missionary work and running the farm and pastoral property, Reuther carried out anthropological research on Diyari (which he called Diari) language and culture. You can find out more information about him at http://missionaries.griffith.edu.au/biography/reuther-johann-georg-rev-1861-1914.

With assistance from his wife Pauline, Reuther compiled a 2,600 page 14 volume handwritten manuscript of Diari (Diyari) language and culture; volumes I to IV comprise a Diari-German dictionary. The manuscript was purchased by the South Australian Museum (SAM) for £75 in 1915 (nine years after Reuther had left the mission in 1906, and after he died by drowning in a horse and cart accident in 1914). It is catalogued as item AA266-09. For information about Reuther and the manuscript see https://www.samuseum.sa.gov.au/collection/archives/provenances/series/aa266-09.

2. History of the Dictionary

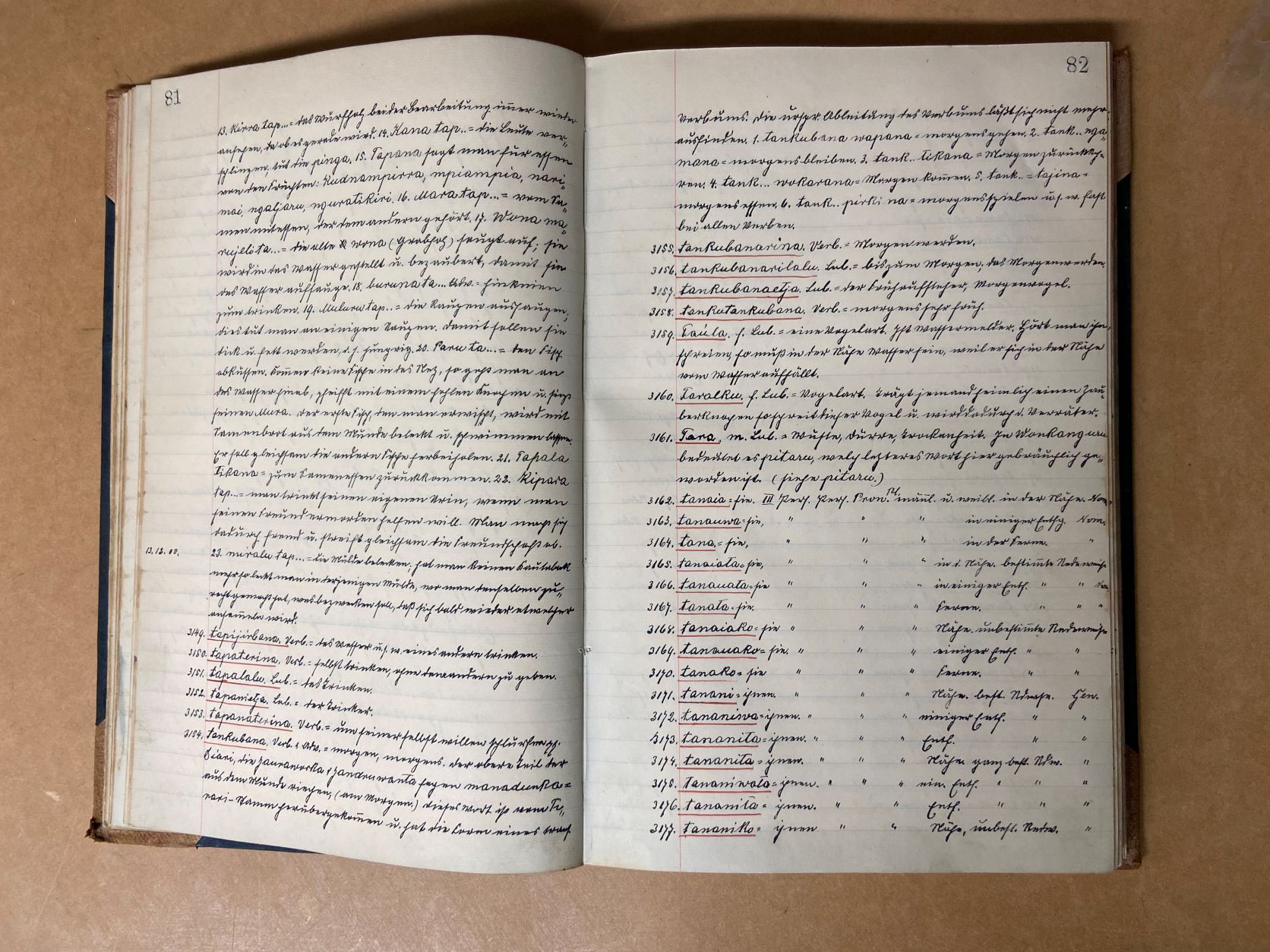

The original Reuther Diari-German materials are held by the South Australian Museum as a set of bound notebooks. Here is a sample showing the handwriting and style of the documents.

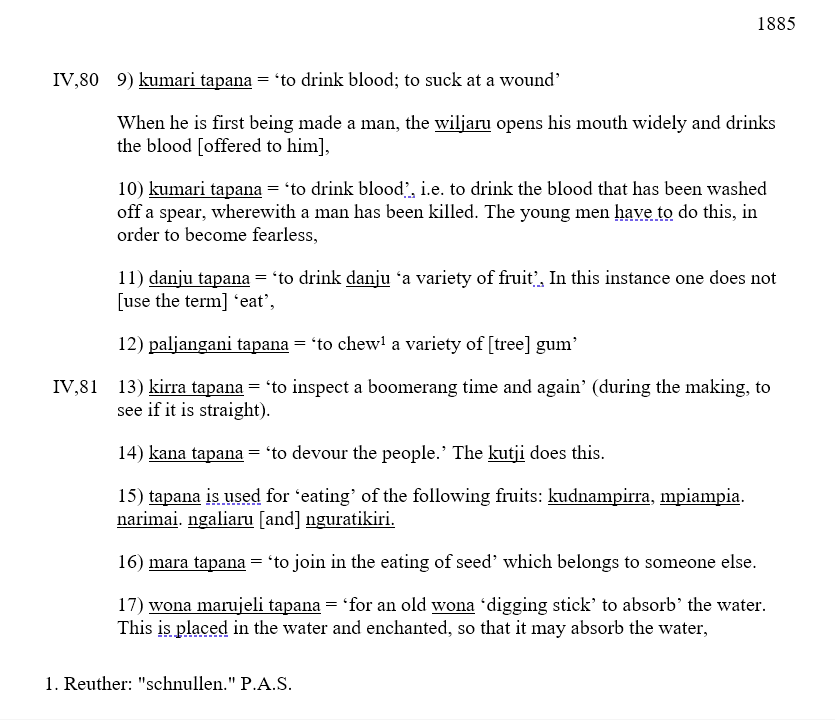

In 1974, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (AIAS, now Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, AIATSIS) provided funding for Pastor Philipp Scherer, the first archivist of the Lutheran Church of Australia, to translate the whole of Reuther’s manuscript into English. The resulting typed document includes the Dictionary in Volumes I to IV amounting to 2,180 pages. Here is a sample (page 1885) from Scherer’s 1974 translation of the dictionary, showing part of Reuther’s volume IV pages 80-81 (compare Figure 2 above).

In 1981 a microfiche of the whole translation was published by AIAS – this is difficult to use because specialist equipment is needed to read the document. In 1989 David Nash and Jane Simpson, working at AIATSIS on the National Lexicography Project, scanned the Scherer translation of the Dictionary using a Kurzweil Discover 7320 Model 30 scanner and optical character reader and created 44 plain text digital files. Simpson proof-read the scanned files and corrected many obvious errors, however many mistakes in the Diyari remained (e.g. ] or J for j, nq for ng, ~ for uninterpreted characters), along with random representations of white space. The resulting files added to the value of the Scherer translation but were still not ideal.

In 1991 I partially edited the proof-read scanned text files in Microsoft Word to correct more errors, especially in the Diyari words, and trying to regularise the formatting.

In 2014-2015 with funding support from the Dieri Aboriginal Corporation, David Nathan processed the Word files to further clean them up and remove inconsistencies. He produced a combined XML-marked-up plain text version, with tags encoding information content, such as <gloss>…</gloss>, plus a Cascading Style Sheet (CSS) which specifies how the file displays (e.g. in a web browser). Paragraphs that are indented in the translation were tagged as <tabp>…</tabp>.

From 2020 to 2023, with assistance from Edward Garrett, Peter K. Austin edited the XML file, adding tens of thousands of content tags, including coding and classifying all 14,924 notes, and 3,879 examples. Garrett refined the CSS to create a pseudo-diplomatic edition of the Dictionary which is published on https://www.diyari.org. Garrett then converted the XML to JSON and indexed the JSON dictionary using the open-source in-memory Redis database. Redis therefore serves as the back-end for this user-friendly interface to Reuther’s dictionary.

The content of entries on this dictionary website (see section 3) can be slightly different from the wording in Scherer’s typescript in the following ways:

- errors in the English translations of entries and examples are corrected. Scherer was a native speaker of German and sometimes his translations show English grammatical mistakes, especially in the use of the articles ‘the’ and ‘a’;

- complex translations have occasionally been divided into the basic meaning plus a Context note, e.g. Scherer’s “to be disturbed, aroused by the rain, (e.g. the grass)” becomes ‘to be disturbed by rain, to be aroused by rain’ Context: e.g. grass;

- some of Reuther’s German translations and comments are now considered offensive or inappropriate, and we have replaced these with more current English alternatives. For example, we give ‘Aboriginal doctor’ instead of “witchdoctor”, ‘people’ instead of “folks”, and remove “heathen” or replace it with terms like ‘pre-contact’ or ‘traditional’.

3. The Dictionary Entries

Entries in the Dictionary vary from simple and quite short to complex and quite long, however they all have the same basic structure:

- a word or phrase in Diyari in the mission spelling (see section 4). These words are in bold;

- the part of speech that the word belongs to, e.g. n for ‘noun’ or ‘v’ for verb. The part of speech determines what endings the word can take, e.g. tenses (time specification) can only be added to verbs;

- a translation in English of the basic meaning, in italics;

- Spelling – the components of the word or phrase in modern Diyari spelling. If Reuther’s word is not known today then no modern spelling is given;

- Grammar – any additional grammatical information;

- Etymology – these are Reuther’s suggestions of the historical origin of some words. Most of his comments are, unfortunately, rather fanciful and unreliable;

- Notes – various kinds of additional information about the use of the word or phrase may be given. This includes Context, which indicates specific contexts of use, Ethnography, which describes socially and culturally significant meanings or uses, and Editor, which are comments by Peter K. Austin who edited the Dictionary. The Notes are classified and can be viewed and searched via the Notes tab at the top of the webpage;

- Mythology – this is information about the muramura ‘ancestral beings’ associated with some words and expressions, and sometimes significant places related to them;

- Comparative – words and expressions in neighbouring languages spoken near Diyari country. These were in use at the mission in Reuther’s time. The other languages given include Wangkanguru, Arabana, Kuyani, Yandruwandha, Yawarrawarka, Thirari, Ngamini, and occasionally Pilardapa;

- Subentries – these are words or expressions related to the main entry and include special idiomatic uses or frequent word combinations. They are numbered in order of presentation;

- Examples – these show sentences where the subentry words are used, together with a translation of the whole sentence into English. The examples are given in a light-coloured box. If you use Search to find Diyari or English words you can then click on “find examples” for each result of your search.

4. Spelling

The German missionaries developed a spelling system for Diyari which became a standard for all materials written in the language from about 1890, including the Dieri Bible, published in 1897. The spelling used by Reuther more-or-less follows the mission orthography, but with quite a bit of inconsistency and variation. To search this online Dictionary you need to use Reuther’s spelling, and sometimes you may need to try several alternatives to find the Diyari word you are looking for. Searching by English meanings may help.

Reuther shows the following variations:

p and b, t and d, k and g, r and rr, o and u, i and e

Reuther’s j is the sound we now spell as y, tj is now written ty (and sounds like ch in church), nj is now written ny (and sounds like the n in new). So, for example, ‘kangaroo’ in Reuther’s spelling is tjukuru whereas the modern spelling is tyukurru.

Reuther’s t and d do not distinguish sounds that are quite different in Diyari, resulting in words being spelled the same by him where they would be different in the modern spelling, e.g. kadi for both kardi ‘brother-in-law’ and karti ‘raw, uncooked’, terti for both thati ‘middle’ and thardi ‘thirsty’.

Similarly, Diyari has three ‘r-sounds’ but Reuther does not distinguish them, and his r and rr can stand for any of these sounds. This can sometimes lead to confusion, e.g. nguru ‘another’ (for nguru) and nguru ‘strong’ (for ngurru), or baru ‘yellow’ (for paru) and paru ‘fish’ (for parru).

In the Dictionary entries the modern spelling is given as “Spelling”, where it is known (some of Reuther’s words have not been able to be checked with people who speak Diyari).

5. Other Materials

Austin has published the following articles and book on the Diyari language. They are available as PDF files for free download:

- a grammar of Diyari (the 2021 second edition is available for free download here);

- an article on the classification of Diyari and neighbouring languages;

- an article on the history of the language and its use;

- an article about postcards written in Diyari;

- stories in Diyari, with English translations, some co-authored with Ben Murray — see here;

- with Luise Hercus and Philip Jones, a biography of Ben Murray, one of my teachers;

- an article on digitisation and value-adding to the Reuther-Scherer manuscript that has resulted in this website.

Information about the Diyari language and culture is available on the blog Ngayana Diyari Yawarra Yathayilha ‘We are all speaking Diyari now’ which presents information and language lessons. The blog began in March 2013 and has a wide range of posts, including Words, Conversations, Songs, Stories, and Language Lessons. Everyone is welcome to visit, and you can leave a comment about any blog post that interests you.

Peter K. Austin also produces a podcast called Dieri Yawarra ‘Diyari Language’ and you can listen to episodes at https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/peterkaustin01/episodes. If you have the Spotify app on your phone, mobile device, or computer search for Dieri Yawarra and click Follow to listen and get regular updates as new episodes are published.

6. References

- Austin, Peter. 1981. A grammar of Diyari, South Australia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Austin, Peter. 1982. The deictic system of Diyari. In Jurgen Weissenborn & Wolfgang Klein (eds.) Here and there: cross-linguistic studies on deixis and demonstration, 273-284. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Austin, Peter. 1986. Diyari language postcards and Diyari literacy. Aboriginal History 10, 175-190. http://www.peterkaustin.com/docs/Austin_1986_AH.pdf

- Austin, Peter. 2004. Chapter 136 Diyari (Pama-Nyungan). In Geert Booij, Christian Lehmann, & Joachim Mugdan (eds.) Morphology: A Handbook on Inflection and Word Formation, 1490-1500. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Austin, Peter K. 2013. A Dictionary of Diyari, South Australia. MS, SOAS, University of London. http://www.peterkaustin.com/docs/Austin_1986_AH.pdf

- Austin, Peter K. 2014. And still they speak Diyari: the life history of an endangered language. Ethnorema 10, 1-17. http://www.peterkaustin.com/docs/Austin_1986_AH.pdf

- Austin, Peter K. 2021. A Grammar of Diyari, South Australia. 2nd edition, version 2.10. MS, SOAS, University of London. http://www.peterkaustin.com/docs/Austin_1986_AH.pdf

- Austin, Peter K. 2022. Making 2,180 pages more useful: the Diyari dictionary of Rev. J. G. Reuther. To appear in Eda Dehermi & Christopher Moseley (eds.) Endangered Languages in the 21st Century . London: Routledge. http://www.peterkaustin.com/docs/Austin_1986_AH.pdf

- Murray, Ben & Peter Austin. 1981. Afghans and Aborigines: Diyari texts. Aboriginal History 5, 71-79. http://www.peterkaustin.com/docs/Austin_1986_AH.pdf